The discovery of interferon in the circulation of people with AIDS.

This is another historical account. It’s about interferon and HIV.

Interferon is produced in response to viral infections as a first line of defence. But in addition to its antiviral properties interferon also has widespread effects on the immune system and elsewhere, some of which can be harmful if prolonged. Therefore mechanisms come into play to turn interferon production off after some days as other antiviral responses come into play.

HIV and disease causing SIV infections are different to other viral infections in that the production of interferon is not turned off; it continues to be produced, sometimes at very high levels. The prolonged presence of interferon contributes to the disease process and is a factor in the loss of CD 4 cells.

As early as 1983 a suppressive effect of interferon on CD4 proliferation had been noted and published. Stuart Schlossman who was one of the first to devise the current method to identify T cell subsets was an author, yet there probably is no reference to this work in the literature dealing with interferon as a treatment for AIDS.

Finding interferon in people with AIDS

AIDS was first recognized in 1981. Interferon was found in the blood streams of people with AIDS later that same year, making it one of the earliest of the significant AIDS associated immunologic abnormalities to be noted. Large amounts of interferon were found that were present for very prolonged periods, a situation noted before only in auto-immune diseases like lupus.

In this post I’ll describe how interferon came to be discovered in people with AIDS so early in the epidemic. It’s an interesting story illustrating at least one way in which science can progress, and also a way in which scientific progress can be retarded.

This early discovery prompted a pretty obvious question: could the sustained presence of interferon have anything to do with the pathogenesis of this newly recognized disease? From what was then known about the effects of interferon it was a question that certainly needed to be explored.

But quite remarkably instead of pursuing this lead almost all early efforts were directed at using interferon as a treatment for AIDS. We had the strangest situation where large amounts of interferon were injected into people who already had more than enough of it circulating in their bodies. This seemed a bit like adding insult to injury; not surprisingly it was of no help.

But if interferon was of no use against HIV it has been spectacularly successful against Hepatitis C, curing many people of this infection. It also may still have a place in treating some people whose Kaposi’s sarcoma is unresponsive to antiretroviral drugs, possibly through its ability to inhibit angiogenesis, which is the process of new blood vessel growth.

Although there were lots of reasons to consider that prolonged exposure to high levels of interferon might have something to do with this newly recognized illness even in 1981, serious work on this possibility was delayed for many years. The zeal to administer yet more interferon to treat AIDS is surely part of the reason for this neglect.

It’s only in the past ten years that we have gained some information on how prolonged exposure to interferon can contribute to the loss of CD 4 lymphocytes.

This is how we came to find interferon in people with AIDS.

Early in 1981 I had referred one of my patients to Dr Joyce Wallace. A biopsy taken of lesions seen in his stomach indicated that these were Kaposi’s sarcoma. Joyce called to tell me that she had contacted the National Cancer Institute to help identify experts in New York City who were familiar with Kaposi’s sarcoma because this was the first time she was confronted with this diagnosis (the first time for me as well). She had been told that over twenty gay men had been diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma and that Dr Alvin Friedman Kien at NYU was treating a number of them. I knew Alvin through my association with Jan Vilcek, a long-time colleague in the field of interferon research. Alvin is a dermatologist but also worked in the NYU lab that Jan headed.

I immediately called Jan who confirmed that Alvin was treating a number of gay men with Kaposi’s sarcoma. Jan very kindly allowed me to work in his lab. I then arranged my time so that I worked in the virology lab in the mornings and saw my patients in the afternoon.

I was one of several scientists who thought it likely that cytomegalovirus (CMV) played a role in this newly recognized disease so initially my lab work centered on this virus.

In the early months of the epidemic Alvin had sent blood samples to Pablo Rubenstein at the New York blood center for HLA typing. HLA refers to the human leukocyte antigen system which allows the immune system to differentiate foreign antigens from self-antigens. It’s important in organ transplantation, where a match in HLA antigens between recipient and donor can prevent organ rejection.

HLA typing is important in investigating a newly recognized disease as there is an association of certain HLA types with some diseases, even some infectious diseases.

A serologic method was then used for HLA typing. It depended on the attachment of HLA specific antibodies to HLA antigens on the surface of leukocytes.

HLA typing of our first patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma proved to be difficult because the patient’s own antibodies were already coating the surface of their leukocytes, interfering with the test.

At the same time I had come across a preprint of a paper reporting an important observation by Jan Vilcek. The CD3 antigen is present on the surface of T cells. Jan had reported that an antibody against the CD3 antigen was a powerful inducer of gamma interferon.

As I read this report it occurred to me that Pablo Rubenstein’s observation that antibodies were attached to our patient’s leukocytes could mean that these blood cells were secreting gamma interferon, which we might be able to detect in their sera.

I discussed this possibility with Jan and Alvin and we immediately set out to test the sera of Alvin’s patients. This idea was to bear fruit, but not what we had expected. Rather than gamma interferon, large amounts of alpha interferon were found.

Jan Vilcek has also described this event, which can be seen by clicking here.

Maybe what’s important is to have a reasonable idea that can be tested, not that the idea need be correct. In fact much later, using more sensitive tests gamma interferon was eventually found in AIDS sera.

In the first few years of the epidemic I was able to obtain interferon assays on sera from my patients. Robert Friedman is another colleague from the early days of interferon research with whom I had published work on the mechanism of interferon’s antiviral action. He was - and still is chairman of the pathology department at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, and he also tested my patient’s sera for interferon. Further interferon tests were done by Mathide Krim, then head of the interferon lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer center.

I also was able to obtain quite extensive immunological tests on my patients through my collaboration with David Purtilo at the University of Nebraska in Omaha. As a result I had (and still have) a small database of my own and so was able to produce further evidence for the association of high interferon levels with low CD4 counts, as well as some other associations with interferon. (1).

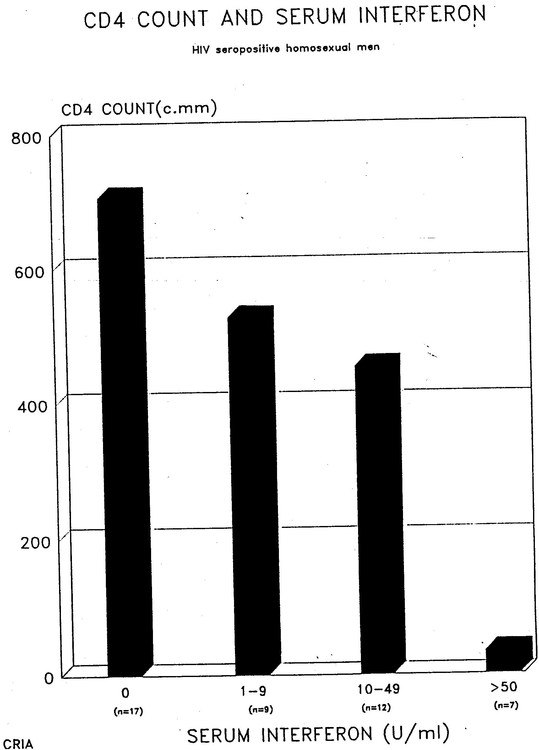

The numbers of patients was not huge but the following graphic shows that 7 people with over 50 units of interferon/ml had under 50 CD4s, 12 people with 10-49 units had under 500 CD4s while 17 people without interferon had about 700.

There are several other interesting correlations. Interferon levels correlate with IgA levels and not surprisingly there is an inverse correlation between CD4 counts and IgA levels.

This was a CRIA presentation in the 1990s from the days when I was the medical director, but the data had first been presented in 1986.

An initial paper describing our findings was turned down by the Lancet.

Our extended findings including data obtained at both Jan Vilcek’s and Bob Friedman’s lab was published in the Journal of Infectious diseases in 1982.

Since there were so many names, it was left to me to decide their order, and I chose that they be listed alphabetically. Thus Gene DeStefano became lead author. He was a technician in Jan’s lab and I believe he went on to become a dentist. This is the title and abstract.

Acid-Labile Human Leukocyte Interferon in Homosexual Men with Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Lymphadenopathy

E. DeStefanoR. M. Friedman, A. E. Friedman-Kien, J. J. Goedert, D. Henriksen, O. T. Preble, J.Sonnabend * and J.Vil?ek (2)

Being familiar with the adverse immunological effects of prolonged exposure to interferon I was puzzled by the attempts to conduct trials of alpha interferon to treat AIDS. This is very different to the benefits of interferon in treating Hepatitis C and some cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

In the case of Kaposi’s sarcoma it was noted that individuals with higher levels of endogenous interferon were unlikely to respond to added interferon.

The zeal to use interferon as a treatment for HIV disease created a strange situation concerning a molecule called beta-2 microglobulin (beta 2M).

In the early years of the epidemic various markers were sought that could act as prognostic indicators. It was soon found that a raised beta 2M level in the serum of patients was an adverse prognostic indicator. High levels were indicative of a poor prognosis. But interferon is the major stimulus for the synthesis and release of beta 2M, something that was known in the 1970s.

In fact the adverse prognostic significance of serum interferon had already been reported early in the epidemic.

A 1991 paper by a noted AIDS researcher, reported studies undertaken to evaluate the hypothesis that elevated beta 2M levels were associated with the production of interferon although this association had been well known for about 20 years. Beta 2M levels can be elevated in certain conditions where interferon is not detectable. But even before the onset of the epidemic we knew that when interferon levels are elevated we expect to see increases in beta 2M. Nonetheless this particular paper was noteworthy in discussing this association. Few others papers dealing with beta-2M during those years did.

I probably angered a number of investigators when I tried - with the help of Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz to inform people of the risks of receiving very high doses of interferon in clinical trials. We felt that information about interferon should be included in the consent form. We even went to the lengths of taking out a paid advertisement in the New York Native to inform people about potential problems associated with receiving high dose interferon. This can be seen here. Richard Berkowitz has posted the complete ad on his website, Richardberkowitz.com

I repeatedly tried to interest writers on AIDS treatment about the probable contribution of interferon to pathogenesis without success .

Dr Fauci and other investigators tried to explain the paradox of administering interferon to people who already had huge amounts of it in their blood stream by claiming that the endogenous interferon was different. The difference referred to was that the AIDS associated interferon could be partially inactivated by acid, whereas the administered interferon was resistant to acid (3).

But we knew that AIDS associated interferon was neutralized by monoclonal antibodies against administered interferon meaning that the molecules were identical, and the interferon in patients’ blood had the antiviral activity expected of alpha interferon. It certainly was responsible for the beta 2M.

In fact the sensitivity to acid is not a property of the interferon molecule but is conferred by other components. Interferon from patients that is partially purified loses its sensitivity to acid.

It’s now more difficult to undertake studies that can investigate correlations between endogenous interferon levels and various immunological abnormalities. It would have to be done on material stored before AZT was introduced or on individuals not receiving antiretroviral drugs.

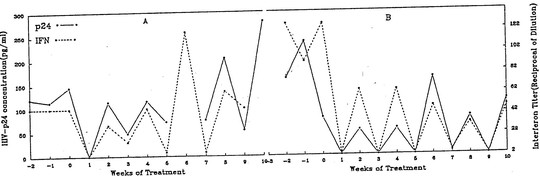

The reason for this is that antiviral therapy promptly removes interferon from the circulation. This is something that the group I worked with at Roosevelt hospital, including Elena Klein and Michael Lange found shortly after AZT was introduced. We had access to sera from clinical trials of AZT. In one of these trials AZT was administered for a week on alternate weeks.

We found that interferon promptly disappeared during the week on AZT, only to reappear just as promptly when AZT was discontinued.

Another report studying sera from the same trial looked at the effect of intermittent AZT therapy on beta 2M. The same saw tooth response of beta 2M was unsurprisingly seen, but my recollection is that the word interferon was not mentioned.

One interesting implication of the effect of AZT (and other antiretroviral drugs) on endogenous interferon levels relates to hepatitis C. It’s been noted that in coinfected individuals starting anti HIV drugs, sometimes there is an increase in liver enzymes as well as an increase in hepatitis C RNA. It’s possible that in some individuals hepatitis C is controlled to some extent by endogenous interferon, and flares up when interferon is removed by the anti HIV drugs. Some researchers have commented on this although I don’t know it this possibility has actually been studied. There are also other reasons why liver enzymes can increase on starting anti HIV drugs.

We presented these results at a meeting I organized in New York in 1990.

This was an attempt to bring clinicians and researchers together to discuss both the roles of interferon in pathogenesis and in treatment.

The innate immune response is a first line of defence against infection coming into play within hours. Secretion of interferon is an important part of this response which also includes the inflammatory response. Innate immune responses are immediate attempts to localize and overcome infections. These beneficial responses last for a brief period because they become harmful if prolonged. There are mechanisms that turn them off. But in HIV infection and in pathogenic SIV infections innate immune responses are not turned off. Persistent immune activation involving the adaptive immune system as well is at the heart of HIV disease pathogenesis.

Several important research questions that I’m sure are being pursued are: Why is the interferon response not turned off in HIV disease? Why does the innate immune response continue to be activated? What are the mechanisms that normally turn off interferon production and why are they not working?

The precise role of interferon in contributing to CD4 loss remains to be worked out, although several mechanisms by which this can occur have been elucidated.

We did not know about the role of persistent immune activation in the earliest years of the epidemic, but by 1983 we had evidence that interferon suppressed the proliferation of CD4 lymphocytes. Even before that time we knew that interferon could cause leukopenia, low white blood counts.

Even in the earliest days we had reason enough to be cautious in administering interferon to people who already had low white blood cell counts let alone suppressed CD4 numbers.

There was also reason enough to explore the possibility that the continued secretion of interferon played a role in the pathogenesis of this disease.

But sadly, for years there was almost no work on identifying what induced such high levels of interferon and on determining which cell produced it, and on elucidating its effects. Nor was there a demand for such studies. It took over twenty years since interferon was first identified in AIDS sera for work to be undertaken to identify the ways in which it can contribute to pathogenesis.

There is still much to be learned, and hopefully the findings can be translated into new therapeutic possibilities.

The reasons why the role of interferon in pathogenesis was neglected for so long are undoubtedly multiple and complex. But one reason for this neglect was the early enthusiasm to administer it as treatment for AIDS.

I have chosen these three references describing different effects of interferon from a growing literature to illustrate what we are beginning to learn about interferon’s role in the pathogenesis of HIV disease.

1. Herbeuval JP, Shearer GM. HIV-1 immunopathogenesis: How good interferon Turns Bad.Clinical Immunology (2007); 123920:121-128

2. Boasso A,Hardy AW et al. HIV-1 induced Type 1 interferon and Tryptophan Catabolism Drive T Cell Dysfunction Despite Phenotypic Activation. PLoS ONE (2008); 3(8): e2961

3. Stoddart CA, Keir ME et al. IFN-?-induced upregulation of CCR5 leads to expanded HIV tropism in vivo, PLoS pathogens (2010); 6(2) e1000766

(1):

Sonnabend J., Saadoun S., Griersen H., Krim M., Purtilo D. Association of serum interferon with hematologic and immunologic parameters in homosexual men with AIDS and at risk for AIDS in New York City.

2nd International Conference on AIDS Paris 1986. Abstract 100

There were several other interesting associations including a positive correlation between IgA and interferon, so needless to say, there is an inverse correlation between CD4 counts and IgA. In the early days I used easily obtainable IgA measurements as an unproven prognostic indicator.

(2)

Some immunologic parameters in homosexual patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) or unexplained lymphadenopathy resemble findings in patients with autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Many patients with SLE have an unusual acid-labile form of human leukocyte interferon (HuIFN-?) in their serum. Sera from 91 homosexual men were tested for the presence of HuIFN. Of 27 patients with KS, 17 had significant titers of HuIFN in their serum. Ten of 35 patients with lymphadenopathy and three of four patients with other clinical symptoms also had circulating HuIFN. In contrast, only two of 25 apparently healthy subjects had serum HuIFN. All 32 samples of HuIFN had antiviral activity on resemble findings in patients with autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Many patients with bovine cells, a characteristic of HuIFN-?, and all of 14 representative samples tested were neutralized by antibody to HuIFN-?. In addition, the HuIFN-? in six of eight representative patients was inactivated at pH 2 and therefore appears to Some immunologic parameters in homosexual patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) or unexplained lymphadenopathy be similar to the HuIFN-? found in patients with SLE. These findings suggest that an autoimmune disorder may underly lymphadenopathy and KS in homosexual men.

.

(3).

I found a transcript of a meeting in New York where Dr Fauci answered questions posed people with AIDS and their advocates, where he explains this.

You can see this at the very end of another article I wrote about interferon and AIDS in 2009 that contains some of the same material in this blog.

http://aidsperspective.net/blog/?p=118

6 Comments

6 Comments