Visual AIDS Program Manager, Ted Kerr, considers Photoshop Activism in the age of Social Media, and Ongoing AIDS

Before Human Rights Campaign, memes, or Facebook there was LOVE, a 1966 silk screen by artist Robert Indiana. He created it based on poems he wrote in 1958 in which he stacked the LO on top of the VE. The image was commissioned by the MOMA for a 1964 Christmas card, spawning hundreds of imitators. In the late 1960s Indiana tried to copyright his work, but a federal court ruled that one person could not own a single word.

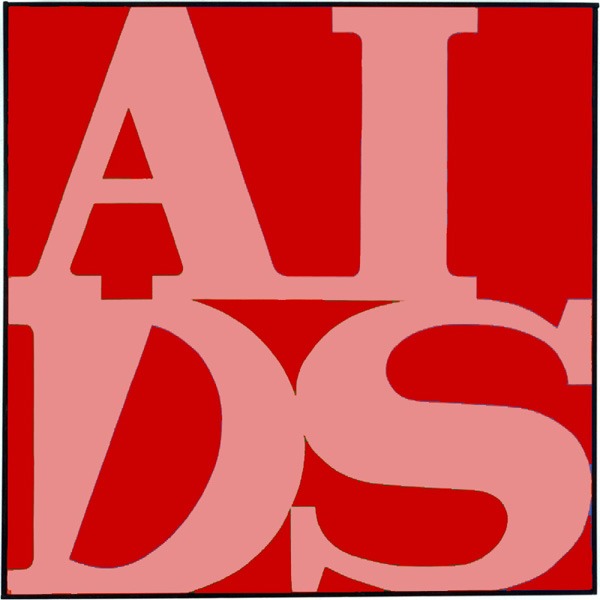

In 1987, General Idea, a collective comprised of artists AA Bronson, Felix Partz (1945-1994), and Jorge Zontal (1944 -1994) remixed LOVE to make AIDS visible to the world. With Partz and Zontal both living with HIV, General Idea worked to make ubiquitous for the world that which surrounded them: AIDS, stacking the AI over the DS. What started off as a small square painting for a benefit soon was a global broadcasting phenomenon called Imagevirus. AIDS-as-logo was on billboards in Germany, subway ads in New York, and a sculpture that still tours, where people are encouraged to graffiti, leave their mark.

“An image is a stop the mind makes between uncertainties,” wrote Djuna Barnes.Artist and writer Gregg Bordowtiz, uses the Barnes quote to explore Imagevirus in his work about the project. He writes, “What General Idea truly did with AIDS was to take hold of its form as a word-image and subject the acronym itself to the most powerful microscopic scrutiny possible in the field of art.”

And scrutinize, the art world did. Around the same time that Imagevirus launched, Gran Fury, a collective of artists including Mark Simpson (d.1994), Tom Kalin, Loring McAlpin, Avram Finkelstein, Terry Riley, Michael Nesline, Donald Moffett, Marlene McCarthy, John Lindell, and Robert Vazquez-Pacheco, were also making art in response to AIDS. Often described as the artistic wing of the seminal AIDS activist group ACT UP, Gran Fury’s work was visceral, and raw. Like Imagevirus, the work Gran Fury did was rooted in repetition, and being part of the urban fabric. Posters like “Art is not Enough” spoke both to the need for the art world to be part of the AIDS movement, and of awareness that art has its limits. It was with this in mind that Gran Fury scrutinized General Idea’s scrutiny. They thought Imagevirus did not go far enough, where was their anger? Gran Fury countered AIDS with RIOT, using the the stacked letters not only to engage General Idea in an arts based conversation about the role of images, but also to also conjure up the spirit of Stonewall, a riot that for many, set off the gay rights movement two decades earlier.

AIDS versus RIOT very much sums up the conversations being had in the art world during the end of the 80’s, the headiest days of the early epidemic. Many artists living with HIV and impacted by AIDS, such as painter Frank Moore (1953-2002), continued to make work that was not immediately understood as political. Where as groups like Little Elvis, fierce pussy, and Gran Fury consciously created work grounded in agitprop. They were frustrated about the lack of work that was being done around AIDS and they expressed it. The work was part of their activism, and part of their self-care. As Tom Kalin said last year at a teach in with the Art and Labor wing of Occupy, the work Gran Fury made was as much for fellow activists--to lift their spirits--as it was for the general public.

What is important to remember is that while AIDS and RIOT created and debated, these artists and activists were not only watching their friends and loved ones die of government neglect, many of them were also dying. There was urgency in the streets that made these conversations not theoretical, but materially important. Flesh was on the line.

Fast-forward a generation or so later, and a tactically similar conversation as was had between Gran Fury and General Idea was playing out across social media yesterday. This time not in paint and printmaking, but in Photoshop and profile pictures.

In response to the Marriage Equality case before the US Supreme Court, web meme guru George Takei posted the photoshopped Human Rights Campaign (HRC) logo that was now red and pink, rather than it’s normal blue and yellow. According to the Chicago Tribune; within hours it had been shared over 20,000 times, soon popping up as people’s new profile pictures, and avatars on twitter. *

By midday, feigning disinterest, offering a queer critique of the HRC and the equality model, or using the meme to raise awareness of other issues, many around the web took to Photoshop to create their own “equality” logo. There was Tilda Swinton sleeping on the equals sign; Against Equality’s clever use of the “greater than” (>) sign; Divine shooting from the center of a red square; and poppers titled to the side, making the equals sign.

Visual AIDS got into the act by photoshopping red and pink both General Idea’s AIDS and Gran Fury’s RIOT, not only to bring it full circle back to LOVE, but more importantly because you cannot talk about equality in America without discussing HIV/AIDS. We wanted--to borrow from Bordowitz, who borrowed from Barnes--to use the meme to “stop the mind” of the various publics invested in pro/anti gay marriage conversations to highlight pressing uncertainties in American life, specifically HIV/AIDS.

While AIDS may not be understood as the death sentence it once was, we are still in crisis. While we as a movement try to embrace the advancements made in terms of prevention (PrEP, PEP and microbicides) and medical care, bodies are still in danger. Activists now are focusing on HIV criminalization; the needs of long term survivors and the newly infected; the injustice around access to care; and why not enough is being done around poverty, housing, education, transphobia, immigration reform, misogyny, racism and other social determinants of health we know lower HIV rates and improve life chances for those most at risk of HIV, due to systemic discrimination.

In the face of all this, Photoshop activism may seem like a silly thing, creating an image, being part of a picture-based conversation. But one of the numerous lessons we can gleam from ongoing AIDS activism, is that expression matters. It is not the be all and end all, but art helps interrupt a conversation, create new ways of thinking, provides a way to heal while acting up, and broadcasts dissent when words are not enough.

In a 1993 speech about the role of art in social movements, Robert Atkins, one of the founders of Visual AIDS, said, “Effective, socially-engaged art practices can help save lives. But only if large and vocal elements within the arts communities help ensure their broadest possible reach.”

Like General Idea and Gran Fury before them, the hundreds of people yesterday that took to their computer to riff off the “equality” logo were engaging in their own scrutiny of this moment, of what is meant by equality and of how lives are really lived in the US. They were attempting to be part of the broadest possible reach. And the work continues. Flesh is still on the line.

* Correction: George Takei did not create the red and pink logo. It was created by the HRC.

Comments

Comments