Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is one of eight members of the herpesvirus family that infect humans and interact with HIV.

CMV and HIV are linked on many levels. In the earliest days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic many of us thought CMV played a key role in the development of the new disease even before it had a name and HIV was discovered. My interest in this virus started when I became aware of unusual symptoms among my gay male patients in New York City around 1979-1980. By early 1981 I knew that physicians elsewhere were seeing similar abnormalities.

In trying to understand what was going on many of us thought that CMV played a role. All my patients were infected with this virus. But in itself this is hardly remarkable, as most individuals have become infected with CMV by the time they reach adulthood. But I knew that an unusually high percentage of my patients were also shedding infectious virus and not just carrying it as an inactive infection.

Initial infection with CMV, as is the case with all of the herpes viruses, is followed by its lifelong carriage. For most of us, this causes no harm to our general health. Humans and herpes viruses have co- existed for so long that they have become well adapted to each other.

But in people with compromised immune systems and infants infected congenitally, CMV infections can be serious, even life threatening.

The importance of CMV and other herpes viruses in HIV infection goes far beyond its ability to cause serious disease. It can also accelerate the progression of HIV disease itself by several different mechanisms, which I’ll outline later.

CMV infection probably almost always precedes the acquisition of HIV because it is transmitted much more easily, and infection with it is much more prevalent.

At last month’s Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in San Francisco, an effect of CMV was described which contributes greatly to our understanding of the role CMV can play in the pathogenesis of HIV disease.

The relationship of immune activation and inflammation to progression of HIV disease was recognized as far back as the 1980s. Cytokines associated with inflammation such as IL-6 and TNF alpha were found, in the mid to late 1980s to be elevated in HIV infection. Around the same time increases in CD8 + lymphocytes that carry a marker for immune activation, HLA DR, were also found to be associated with disease progression.

Valgancyclovir is used to treat CMV infections. It can only work in herpes virus infected cells because, in order to be active, the drug must be changed by an enzyme (thymidine kinase) which is encoded by herpes viruses and therefore only present in cells infect with these viruses.

What was reported at CROI by Peter Hunt and his colleagues, was that treatment with valgancyclovir for 8 weeks resulted in a decrease in both activated CD8+ cells and an important marker of inflammation, C-reactive protein (but not other activation markers).

The importance of infection with CMV and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), another herpes virus in contributing to the immune activation in HIV infection was well described in 2008 in this paper:

“Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences” by V. Appay and D Sauce.

It’s quite technical but very much worth looking at, and can be seen by following this link.

Immune activation and inflammation:

What this tells us is that CMV and other herpes viruses probably contribute very significantly to the immune activation and inflammation characteristic of HIV disease and in this way promote disease progression.

CMV infections are so prevalent it is hard to find HIV infected individuals who are free from it in order to compare them with those who have it. This is easier in pediatric populations. Last year congenitally-infected HIV positive infants who were also infected with CMV could be compared with those who were not. They were reported to have had a more rapid decline in their CD4 percentage, resulting from the increase in CD8 lymphocytes associated with active CMV infections.

Once acquired, CMV, as with all herpes viruses, remains present for life. The infected individual will produce antibodies against the virus. However not all those who are CMV antibody positive are actively infected as measured by detecting CMV virus itself in blood or body secretions by culturing it or by techniques like PCR. Periodic reactivation however does occur.

Using such techniques it is possible to compare HIV disease progression in people with or without active CMV infections.

As early as 1986 an article published in AIDS Research which I was then editing suggested a correlation of CMV viremia with a poor prognosis for HIV infected individuals. Since then several additional studies have suggested the same thing.

It is difficult to know what comes first; are active CMV infections accelerating HIV disease or is it the other way around? It’s most certainly both, and I’ll address this later.

There are several mechanisms that have been uncovered that explain how herpes viruses and HIV can interact. But first a few words about HSV-2.

The reason why HSV-2 has been studied so extensively in relation to HIV is that it is the most common cause of genital ulcers (HSV-1 can also do so). There was a reasonable speculation that a genital ulcer might provide a portal of entry for HIV, an idea that seemed even more plausible when it was found that CD4 lymphocytes, - the target of HIV, were concentrated in the ulcers. In the case of the HIV infected partner, transmission might be facilitated because of the high concentration of virus in the ulcer. If this were so then drugs that inhibit herpes viruses such as acyclovir (Zovirax) or valacyclovir (Valtrex) might lessen the chances of HIV transmission by reducing recurrences of genital ulcers.

It seems however that this apparently reasonable assumption may not be correct.

A few years ago a large Partners in Prevention study found that while Zovirax did what was expected in reducing herpetic genital ulcer recurrences, it did not prevent HIV infection. However Zovirax or Valtrex did reduce HIV viral loads.

Just this week there is a report in the Lancet indicating that treatment with Zovirax slows the progression of HIV disease.

Treating HIV infection with drugs for HSV-2 infection? This is the title of a comment in this week’s Lancet. It refers to the report of the study in the same issue where 3381 people dually infected with HSV-2 and HIV were randomly assigned to receive either acyclovir or placebo at 14 sites in southern and east Africa, and followed for up to 24 months. HIV disease progression was measured by a composite end point,- including reaching a CD4 count of less than 200. By this measure, acyclovir reduced the risk of HIV disease progression by 16%.

I don’t know why the authors just focussed on HSV-2. Compared to HSV-2, HSV-1 infections are more prevalent and may be even more sensitive to acyclovir. Effects resulting from a suppression of other herpes viruses must also be considered, although they are more resistant to acyclovir with CMV being the most resistant.

The differing susceptibility of herpes viruses to acyclovir is generally in this descending order of sensitivity: - HSV-1, HSV-2, Varicella -Zoster virus (VZV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and CMV.

It’s most likely that anti herpes drugs can exert a suppressive effect on HIV indirectly by inhibiting the systemic effects herpes viruses have in promoting HIV replication and accelerating HIV disease progression. HIV disease progression is enhanced by the contribution of herpes virus infections to immune activation, and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with these infections.

In addition, cells infected with herpes viruses express receptors on their surface that HIV can use if attached to antibody. These are called Fc receptors and can provide a way for HIV to get into a cell that does not have CD4 molecules on its surface.

HIV and herpes viruses can activate each other by a process called transactivation in cells where they are both present.

There are additional possible mechanisms by which herpes virus infections can promote HIV replication including effects herpes viruses, particularly CMV, have on the immune system.

I have mostly listed ways in which herpes viruses can enhance HIV, but equally important are the effects of HIV in promoting herpes virus infections. All herpes virus infections can be much more serious in HIV infected individuals. CMV disease can be life threatening and cause blindness, HSV 1 and HSV 2 ulcers can be extensive, as can shingles, EBV can cause lymphoma and of course HHV 8 can cause Kaposi’s sarcoma. We should also expect that the HIV enhancing effects of serious herpes infections to be that much greater.

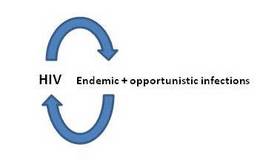

Because herpes viruses and HIV can promote the replication of each other we can look at their interaction as having features of positive feedback systems.

Here is a drawing that shows such a relationship.

HIV promotes herpes replication which in turn promotes further HIV replication and so the cycle can accelerate.

This mutual enhancing effect is not confined to herpes viruses. Many other infections are also associated with the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines which accelerate HIV replication which then increases susceptibility to further infection. Some infections, particularly tropical infections are also associated with an increased expression of chemokine receptors on the cell surface that HIV uses for entry, and can themselves be mildly immunosuppressive.

So the positive feedback elements are broader than the reciprocal interactions between HIV and herpes viruses. They include opportunistic and endemic infections.

An implication of the reciprocal enhancing effects of HIV and other infections is that the control of these other infections is then crucial to the control of HIV. In developed nations herpes infections are the most important. Fortunately we have well tolerated drugs that can effectively suppress herpes viruses. There is presently a trial underway of the effect of Valtrex on HIV viral load in HSV 1 and 2 infected people (which would be just about everybody) that may shed further light on this.

In developing countries there are additional considerations because of the prevalence of different endemic infections. Many can be controlled by relatively inexpensive traditional public health measures, so a support for these interventions will not only improve the health of populations but is also relevant in the fight against AIDS.

I did write about this in a previous Poz post: Endemic infections in Africa have everything to do with HIV/AIDS.

I also wrote something about herpes viruses and HIV last year:

http://aidsperspective.net/blog/?p=381.

Fortunately we have effective drugs to prevent and treat serious herpes virus infections. And we may soon know with confidence if herpes virus infections contribute to HIV disease progression. If they do, an additional therapeutic approach is already available.

In conclusion, it is of some interest to recall that the first published proposal for the use of condoms to prevent this new disease preceded the discovery of HIV was mainly based on interrupting the transmission of CMV but also of other sexually transmitted pathogens. With two of my patients, Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen, who were tireless in their efforts to mobilize a response to the emergency, we thought of ways in which the spread of CMV could be limited. I knew that re-infection with this virus was possible. People receiving a kidney transplant often developed a mononucleosis- like illness after a blood transfusion. It was believed that this was caused by CMV in the transfused blood. When techniques were developed that could distinguish the DNA of different CMV isolates it was found that many cases of mononucleosis were actually caused by a reactivation of the CMV that was already carried by the patient. CMV could be so frequently isolated from the secretions of my patients that I thought it possible that continued re-infection with CMV was involved. Because CMV can be so readily isolated from semen, condom use was proposed in “How to have sex in an epidemic. One approach” (May,1983). In those dark days we only had theories to guide us.

I’m adding a short postscript listing the eight herpes viruses that can infect humans.

Because of the long co-existence of these viruses and their hosts, evolutionary forces have resulted in a mutual adaptation to each other, so that most people carry these viruses for a lifetime in good general health. Initial infection may be associated with a transient illness, and is followed by lifelong carriage of the virus, generally in a latent state. Characteristically the virus is reactivated periodically which allows it to be transmitted to a new host. Recurrences may or may not be associated with symptoms. For example shingles is a reactivation of the herpes virus that caused chickenpox when infection first occurred.

These are the eight human herpes viruses.

HHV -1: HSV-1 causes typical recurrent cold sores but ulcers can occur anywhere including genitally.

HHV-2: HSV-2 typically causes recurrent genital ulcers, but ulcers can occur elsewhere.

HHV-3: Varicella-zoster virus. VZV causes chickenpox on initial infection and shingles when it is later reactivated.

HHV-4: Epstein-Barr virus can cause infectious mononucleosis. It can also cause lymphoma nasophayngeal carcinoma and a fatal lymphoproliferative syndrome in certain hosts with a specific genetic abnormality.

HHV-5: CMV

HHHV-6 and HHV-7:

HHV-8: Kaposi’s sarcoma associated virus.

Comments

Comments